Aneurysmal SAH/ruptured aneurysm

Approximately 85% of non-traumatic SAH develop in the setting of an aneurysm. Frequency of aneurysms - postmortem 2-5%, angiography 1-10%; the female:male ratio is 3:2. 12-15% of patients have a positive family history. The incidence of aneurysmal hemorrhage is estimated at 5-10 cases per 100,000 population per year.

In the development of aneurysm, in addition to the familial or genetic components, the role of hemodynamic causes and risk factors such as smoking and hypertension is considered primarily. The majority of intracranial aneurysms are located in the area of the blood circulation of the anterior cerebral arteries (circle of Willis - about 80-90%), up to 15% - in the vertebrobasilar region (the area of blood circulation of the posterior cerebral arteries). Extradural aneurysms of the internal carotid artery (caudal part of the ophthalmic artery) do not pose a significant risk of bleeding, but if the size is appropriate, they may also become symptomatic (eg, loss of cranial nerve function).

The risk of hemorrhage from all aneurysms combined is approximately 1% per year. The most important factors influencing the risk of aneurysm rupture include:

- Size and location (risk of rupture within five years according to modified data from the ISUIA-2 study: aneurysm size < 7 mm: anterior circulation < 1%, posterior circulation 2.5%

- aneurysm size 7-12 mm: anterior circulation area 2.6%, posterior circulation area approximately 15%

- aneurysm size 13-24 mm: anterior circulation area 14.5%, posterior circulation area 18%

- aneurysm size >24 mm: both areas of blood circulation 40-50%)

This means that patients with large (>12 mm) irregularly shaped aneurysms located in the posterior circulation have a high risk of aneurysm rupture each year, clearly greater than 10%.

How is it diagnosed?

A neurologist can suspect the presence of SAH in a patient based on the characteristic clinical picture of the pathology. However, to make an accurate diagnosis, there is not enough information about what subarachnoid hemorrhage is and how it manifests depending on the location of the lesion. In addition to external signs, the doctor must have the results of laboratory and instrumental tests.

The most informative diagnostic methods include:

- CT scan. Brain CT is the most accurate examination method for suspected SAH. Tomography makes it possible to detect cerebral edema, bleeding into the ventricles and subarachnoid membrane, foci of ischemia, etc. On days 1-2 after a stroke, the sensitivity of the method is more than 95%, on days 2-3 - 80-85%, and 6 days after hemorrhage - less than 30%. For delayed diagnosis of SAH, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain is a more informative method.

- Transcranial ultrasound and duplex examination of cerebral vessels. Catheter diagnostics of cerebral vessels makes it possible to establish the source of bleeding, diagnose vasospasm and determine the need for urgent surgical intervention. If the source could not be detected during the first examination, a repeat vascular ultrasound is recommended 20-28 days after SAH.

- MRI angiography. If there are contraindications to intravascular examination of the cerebral arteries, non-invasive angiography is performed using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. In case of severe pathology, the study is carried out after stabilization of the patient's condition.

- Puncture of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Characteristic signs of SAH are a reddish or xanthochromic color of the cerebrospinal fluid, a high concentration of red blood cells (more than 100,000 units/ml), increased levels of protein and white blood cells (neutrophils). A cerebrospinal fluid sample is necessary in cases where it is not possible to perform a CT scan or tomography does not show cerebral changes against the background of a characteristic neurological picture. If there is a high risk of brain dislocation (displacement), this manipulation is prohibited.

Important information: How to take Glycine for stroke and for prevention

Non-aneurysmal and non-traumatic SAH

Approximately 10-20% of subarachnoid hemorrhages are neither aneurysmal nor traumatic. The reasons in such cases are:

- Hemorrhage from the prepontine/perimesencephalic veins (“perimesencephalic” SAH)

- Arteriovenous malformations

- Dural fistulas

- Redistribution of blood during intraventricular hemorrhage

- Vasculitis/arteritis: caused by a pathogen (for example, mycotic aneurysms, syphilis, borreliosis),

- immune-mediated (eg, CNS angiitis, Wegener's disease, polyarteritis nodosa, neurosarcoidosis, Behçet's disease)

Preventative measures to prevent relapses

To minimize negative consequences, it is necessary to remember how to prevent subarachnoid hemorrhages:

- A nutritious diet, in which the body receives large quantities of fruits and vegetables, reduces the amount of fatty and fried foods.

- Refusal of drugs, alcohol, cigarettes.

- Gradual introduction of moderate exercise (swimming, race walking, jogging).

- Regular walks.

- Monitoring blood pressure (find out how to choose a tonometer for home use) and blood glucose concentration.

These preventive measures reduce the risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

A timely diagnosis and treatment measures allow patients to recover . But negative consequences of subarachnoid hemorrhage, which are life-threatening, occur in 80% of patients. The use of preventative measures will help prevent this.

This video presents a lecture on the treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage:

Source: oserdce.com

Symptoms and signs of subarachnoid hemorrhage

The following symptoms are characteristic primarily of aneurysmal SAH:

- Acute onset of severe to maximally intense headaches (“headaches like I’ve never had before”)

- Approximately 25% of patients develop sentinel bleeding with short-term headaches in the run-up to aneurysmal SAH;

- Meningism

- Impaired consciousness

- Vomiting/nausea, autonomic disorders Loss of cranial nerve function and other neurological deficits.

Subarachnoid hemorrhages are classified using the Hunt and Hess scale or the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) classification.

Reasons for the development of pathology

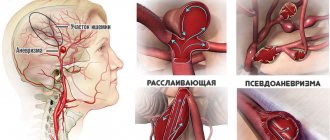

Spontaneous or, as it is commonly called in medical terminology, primary hemorrhage (SAH) occurs, as a rule, due to the rupture of an aneurysm of certain superficial vessels of the brain. Somewhat less frequently, it is observed with rupture of atherosclerotic or mycotic aneurysms, arteriovenous malformation, or hemorrhagic diathesis. With traumatic brain injuries, subarachnoid cerebral hemorrhages are also very common.

In approximately half of the cases, the cause of intracranial hemorrhage is aneurysms of blood vessels located in the brain. These pathological formations can be congenital or acquired. Visually, an aneurysm is a saccular formation on the wall of a vessel, in which the neck, body and bottom are distinguished. The diameter of such a vascular sac, as a rule, ranges from a few millimeters to a couple of centimeters. Aneurysms larger than 2 cm in diameter are considered giant. Subarachnoid hemorrhage (ICD code I60) occurs equally in both men and women, and is very often hereditary.

Problems/complications of SAH

- Impaired consciousness

- Worsening neurological deficits (due to, for example, cerebral edema, secondary ischemia, cerebrospinal fluid circulation disorders)

- Epileptic seizures (up to 10% of patients)

- Recurrent hemorrhages in aneurysmal SAH (4-6% within the first 24 hours, 40% within the first three weeks)

- Vasospasms with secondary ischemia (late ischemic neurological deficit); onset usually from day 3, symptomatic vasospasms = new onset neurological deficit (present in 20-50% of patients with SAH); symptomatic vasospasms are associated with approximately 10% mortality.

- Disturbances in the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid with hydrocephalus - up to 25% of patients (also with a long course)

- Cardiopulmonary dysfunction: arrhythmias (tachy/bradycardia), cardiac ischemia, heart failure, pulmonary edema in the early phase (several hours after onset), which lasts several weeks

- Electrolyte imbalances: cerebral salt wasting syndrome and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, as well as disorders of the humoral nervous regulation of water and electrolyte balance → clinically relevant hyponatremia in approximately a third of patients

- Complications during and after aneurysm therapy: clipping: vascular stenosis with clips, thrombosis, vessel rupture

- coil application: aneurysm perforation (approximately 2-8%), occlusion of the supporting vessel (approximately 3-5%), rupture and dislocation or migration of coils (approximately 1-5%), recurrent hemorrhage from incomplete (< 90% of aneurysm volume) closed aneurysms (approximately 6-27%), thromboembolism (approximately 5-25%),

- vascular dissection

Description

Subarachnoid stroke develops due to hemorrhage in the space between the arachnoid and pia mater of the brain. This space is filled with fluid and blood entering there provokes an increase in intracranial pressure. As a result, a violation of the soft membrane of the brain begins with manifestations of non-infectious meningitis.

The response to hemorrhage is vasospasm, which can trigger the development of ischemic stroke in certain parts of the brain. The consequences of the pathology are most often severe, and the recovery process is long and complex.

Excursion: monitoring/diagnosis of vasospasms

- Clinical examination is only possible if the patient is conscious, when a disturbance of consciousness is noted, then parenchymal damage has probably already occurred. Clinical deterioration is differentiated from the effects of sedatives, repeated hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, cerebral edema, metabolic disorders, infections

- Continuous EEG is sensitive to interference, experience required

- Angiography (gold standard) - requires qualified personnel, takes a lot of time, potential risks during transportation

- Transcranial Doppler ultrasound (Vmax> 120 cm/sec or increasing Vmax> 50 cm/sec within 24 hours) depends on the examiner, angular error, specificity approximately 50-60%

- Transcranial duplex sonography depends on the examiner performing the examination

- CT angiography, CT perfusion, MR angiography, MR perfusion - “snapshot”, potential risks during transportation; qualified personnel required; First of all, “functional” visual methods have not yet been sufficiently evaluated.

- Measurement of cerebral oxygenation, cerebral blood flow, microdialysis: labor-intensive methods, partly experimental

Drugs

Drug treatment is symptomatic. The list of medications should only be compiled by the attending physician in consultation with specialists. The most common drugs prescribed for this pathology are:

- Diazepam to reduce excitability.

- Cadeine and analgin for headache relief.

- Dehydrating medications to relieve hydrocephalus.

- Coagulants.

- Neotropic drugs.

- Peptides.

- Other drugs depending on symptoms.

Treatment of subarachnoid hemorrhage

Patients with SAH in the initial phase require continuous monitoring (consciousness, neurological status, parameters of the cardiovascular system, temperature, laboratory parameters, daily monitoring by transcranial Doppler ultrasound from 2/3 days).

Hemorrhage into the subarachnoid space is a major disease, so treatment of hemorrhage-related complications significantly influences the outcome. Treatment of aneurysm is important for secondary prevention, but represents only one element of overall therapy.

Conservative therapeutic measures for (aneurysmal) SAH

- Prevention of thrombosis: antithrombotic stockings, passive physiotherapy; Caution: Heparin therapy may lead to secondary bleeding

- Reduction of fever at temperatures >38.5°C

- Treatment of hyperglycemia

- Prevention of surges in intracranial pressure during pushing, gagging, coughing -> bed rest, antimimetics, laxatives; for a severe cough, sometimes antitussives, and for mucus, aspiration of mucus and mucolytics (for example, ACC)

- Pain therapy and sedation: Adequate and continuous or intermittent (at regular intervals) analgesia is required using peripheral (eg, paracetamol, metamizole) and/or central analgesics (opiates). Excitement and pain may be associated with significant increases in blood pressure and an increased risk of rebleeding. Caution: Excessive sedation makes clinical assessment difficult.

- Treatment of hypertension: Significantly elevated blood pressure parameters in the case of an untreated aneurysm may be associated with an increased risk of rebleeding. With arterial hypotension, on the contrary, there is a danger of decreased perfusion with secondary ischemia in areas where autoregulation has ceased. Blood pressure therapy is recommended only for severe hypertensive crises and should be selected according to individual pre-SAH blood pressure levels, as well as concomitant diseases and the patient’s age. To prevent decreased cerebral perfusion, it is always recommended to lower blood pressure carefully with well-controlled medications (eg, intravenous urapidil, beta-receptor blockers).

- Therapy of cardiac disorders: mainly during the first 48 hours, cardiac arrhythmias, ECG changes (for example, changes in the ST segment, AV block), increased levels of cardiac enzymes and limited pumping function of the heart are often observed, up to pulmonary edema and complete cardiac failure. . Since the changes are usually transient and recovery should be expected after a few days, it is advisable to carry out symptomatic therapy first of all.

- Treatment of fluid and electrolyte imbalances: After SAH, significant sodium reduction with hypovolemia often develops. To prevent a decrease in cerebral perfusion, the goal should always be to achieve normovolemia. It is primarily recommended to use crystalloid isotonic infusions - daily requirement: -30 ml/kg body weight → for example, 2.5-3.5 l of 0.9% NaCl solution. Fluid administration should be tailored to individual needs (eg, decrease for heart failure, increase for fever [approximately 500-1000 ml per 1°C increase in temperature]). Observation is carried out by monitoring cardiovascular parameters (ECG, blood pressure, CVP, according to indications PiC-CO-system, pulmonary artery catheter), as well as fluid balance (→ bladder catheterization).

Attention: blood pressure parameters may increase in case of complications (for example, recurrent hemorrhage, intracranial pressure), as well as in case of pain.

In case of electrolyte imbalance, oral and/or intravenous replacement of missing electrolytes is prescribed, diuretics are reduced, if necessary, the composition of infusions is changed taking into account the deficiency of electrolytes (for example, hypertonic solutions of table salt), and laboratory monitoring is carried out daily.

- Prevention of secondary ischemia in aneurysmal SAH—vasospasm therapy: nimodipine: According to the current state of research, only oral nimodipine (6x60 mg/24 hours for three weeks from diagnosis) is recommended for the prevention of vasospasms. The effect of intravenous nimodipine is not completely justified and is fraught, first of all, with the risk of a drop in pressure with the risk of a decrease in cerebral perfusion. Moreover, despite the fact that the so-called “MH” therapy (hemodilution: hemoglobin> 10 g/dl, hematocrit 30-35%, colloidal infusions; hypervolemia: crystalloid infusions 3000-10000 ml/24 hours; hypertension: mean arterial pressure >70 mm Hg) is repeatedly recommended and used in cases of confirmed vasospasm. There are no completed studies that would show a clear advantage of this therapy in the treatment of vasospasms and the prevention of secondary ischemia.

Endovascular therapy for unresponsive vasospasms or patients with severe underlying cardiac disease who cannot be transported to specialized centers for nimodipine therapy includes balloon dilatation, intra-arterial administration of vasodilators such as calcium channel blockers, papaverine (no evidence-based studies, complications: rupture, occlusion, vessel dissection, hemorrhage, provocation of bleeding from an aneurysm).

- Treatment of hydrocephalus: since disturbances in the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid in approximately 30% of patients develop during the first three days, strict observation is necessary, and if hydrocephalus is confirmed with increased intracranial pressure and corresponding clinical symptoms, an external cerebrospinal fluid drainage (ECD) is indicated. According to indications, NVD is installed before the intervention, since then anticoagulant therapy is sometimes necessary (for example, after stenting).

In approximately V* patients, hydrocephalus occurs with a delay of several weeks, and the rate of its development does not depend on the therapy performed (coil or clipping).

- Treatment of seizures: Anticonvulsant therapy is indicated only after the first seizure. Prophylactic antiepileptic therapy is not indicated.

Surgical/interventional therapeutic measures for aneurysmal SAH:

Due to the high risk of recurrent hemorrhage in the early phase of SAH after aneurysm rupture, treatment should be carried out within the first 72 hours (before the onset of vasospasms). Indications for therapy and the choice of treatment method (coil or clipping) depend on the location, size, shape and morphology of the aneurysm. The decision should be made jointly by experienced neuroradiologists and neurosurgeons.

The rationale for ideal aneurysm therapy (neurosurgical clipping or endovascular coiling) is lacking. In the ISAT study and Cochrane review, better outcome in patients with ruptured intracerebral aneurysm was shown after coil therapy compared with neurosurgical repair. It should be noted that in this study, treatment was carried out only in cases of ruptured small aneurysms with a narrow neck (without the use of additional devices, such as a stent, balloon), so these results cannot be transferred to the treatment of aneurysms in general. Over a long period of time (6-14 years), there was no significant difference in outcome between both treatment methods, however, the likelihood of recurrent hemorrhage in patients after installation of the coil was slightly higher.

A favorable percentage of occlusion by means of a coil is observed primarily for small aneurysms (< 10 mm) with a ratio of the width of the supporting vessel to the neck of the aneurysm sac > 2:1. In addition, the overall increased surgical risk, localization in the vertebrobasilar blood flow, widespread vasospasm and unsuccessful attempts at clipping are in favor of endovascular therapy (for saccular aneurysms).

Larger aneurysms (>10 mm) with a wide neck relative to the parent vessel, as well as partially thrombosed aneurysms and aneurysms in the region of multiple branches, should expect a relatively low incidence of occlusion with endovascular therapy.

Very small aneurysms (<2.5 mm) are unlikely to undergo endovascular therapy (especially if they still extend from the supporting vessel at a “poor” angle). If the anatomy of the aneurysm is very complex and/or unclear, surgical intervention is indicated.

One review reported achieving >90% primary occlusion with the coil. However, in dynamics, in 20% of cases after installation of the coil, re-opening of the aneurysm is observed with the need for re-treatment in 10% of cases. Aneurysms measuring >10 mm show the highest rate of reopening. In a 2011 study, re-therapy of aneurysms after coil placement was required in only 3% of cases.

The decision to treat an aneurysm should always be individualized because it depends on patient factors (eg, age, comorbidities) as well as the location, size, and morphology of the aneurysm.

Therapy for nonaneurysmal SAH

Treatment of nonaneurysmal SAH depends primarily on the underlying cause of the hemorrhage. There are no specific therapeutic recommendations, so conservative therapy, in particular, comes to the fore. The use of nimodipine in the treatment of nonaneurysmal SAH is not recommended.

Pathology in newborns

Subarachnoid hemorrhage in infants can be associated with birth trauma, has such manifestations as meningeal and hydrocephalic syndrome, as well as focal symptoms that depend on the location of the hemorrhage, appearing immediately after birth.

Moderate hemorrhages in most newborns develop almost asymptomatically or can be detected on the second day. Signs of cerebral hemorrhage in newborns appear as:

- Severe restlessness and general agitation.

- Brain scream.

- Cramps.

- Sleep inversions.

- Strengthening innate reflexes.

- Increased muscle tone.

- Hyperesthesia.

- Jaundice.

- Bulging of the fontanel.

Correct diagnosis and timely treatment help to significantly reduce the risk of the formation of organic pathologies of the brain, contribute to their rapid rehabilitation and minimize the adverse consequences for the central nervous system, which lead to the development of cerebral palsy in children.

Forecast

Despite improvements in therapeutic modalities, approximately 50% of patients with SAH die within the first 28 days, with approximately 25% of patients dying before reaching the hospital. The prognosis, on the one hand, depends on the primary damage.

Patients with a primary coma have the worst prognosis. On the other hand, secondary complications, such as ischemia due to vascular spasms, or disturbances in the circulation of cerebrospinal fluid, can lead to further damage. Approximately 30-50% of affected patients can survive independently for one year after SAH. In addition to motor and speech deficits, patients often suffer from cognitive and affective disorders, as well as hearing and smell impairments.