Epilepsy is a neurological disease that occurs in a chronic form. The disease is expressed by the sudden appearance of convulsive attacks.

The main feature of epilepsy and its difference from other neurological diseases lies in the frequency of manifestations. The disease itself is unstable, and new symptoms may be added to the main symptoms.

Idiopathic epilepsy, which most often manifests itself among other types of neurological disorders, can change throughout a person’s life. And if in childhood its symptoms are the same, then by adulthood they can be completely different. Let's look at how idiopathic epilepsy is dangerous and in what forms it manifests itself.

Content

- 1 Concept of epilepsy

- 2 Relation to epilepsy

- 3 Terminology

- 4 Classification of attacks 4.1 Primary generalized attacks

- 4.2 Partial seizures

- 5.1 International classification of epileptic seizures (ILAE, 1981)

- 8.1 Electroencephalography

- 12.1 Drug treatment of epilepsy

Symptoms of epilepsy

Mental disorders of patients with epilepsy are determined by:

- organic brain damage underlying the disease epilepsy;

- epilepsy, that is, the result of the activity of an epileptic focus,

- depend on the location of the outbreak;

- psychogenic, stress factors;

- side effects of antiepileptic drugs - pharmacogenic changes;

- form of epilepsy (absent in some forms).

structure of mental disorders in epilepsy

| 1. Mental disorders in the prodrome of a seizure | 1. Precursors in the form of affective disorders (mood fluctuations, anxiety, fear, dysphoria), asthenic symptoms (fatigue, irritability, decreased performance) 2. Auras (somatosensory, visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, mental) |

| 2. Mental disorders as a component of an attack | 1. Syndromes of changes in consciousness: a) loss of consciousness (coma) - with generalized seizures and secondary generalized ones b) special states of consciousness - with simple partial seizures c) twilight stupefaction - with complex partial seizures 2. Mental symptoms (disturbances of higher cortical functions): dysmnestic, dysphasic, ideational, affective, illusory, hallucinatory. |

| 3. Post-attack mental disorders | 1. Syndromes of changes in consciousness (stupor, stupor, delirium, oneiroid, twilight) 2. Aphasia, oligophasia 3. Amnesia 4. Autonomic, neurological, somatic disorders 5. Asthenia 6. Dysphoria |

| 4. Mental disorders in the interictal period | 1. Personality changes 2. Psychoorganic syndrome 3. Functional (neurotic) disorders 4. Mental disorders associated with the side effects of antiepileptic drugs 5. Epileptic psychoses |

features of personality changes in epilepsy

1. Characterological:

- egocentrism;

- pedantry;

- punctuality;

- rancor;

- vindictiveness;

- hypersociality;

- attachment;

- infantilism;

- a combination of rudeness and obsequiousness.

2. Formal thinking disorders:

- bradyphrenia (stiffness, slowness);

- thoroughness;

- penchant for detail;

- concrete descriptive thinking;

- perseveration.

3. Permanent emotional disorders:

- the viscosity of affect;

- impulsiveness;

- explosiveness;

- defensiveness (softness, obsequiousness, vulnerability);

4. Decrease in memory and intelligence:

- mild cognitive impairment;

- dementia (epileptic, egocentric, concentric dementia).

5. Change in the sphere of drives and temperament:

- increased instinct of self-preservation;

- increased drives (slow pace of mental processes);

- predominance of a gloomy, gloomy mood.

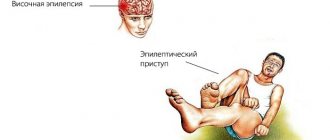

Epilepsy concept

The onset of a single attack characteristic of epilepsy is possible due to the specific reaction of a living organism to the processes that have occurred in it. According to modern concepts, epilepsy is a heterogeneous group of diseases, the clinical picture of chronic cases of which is characterized by convulsive repeated attacks. The pathogenesis of this disease is based on paroxysmal discharges in the neurons of the brain. Epilepsy is characterized mainly by typical repeated seizures of various types (there are also equivalents of epileptic seizures in the form of sudden onset mood disorders (dysphoria) or characteristic disorders of consciousness (twilight stupefaction, somnambulism, trances), as well as the gradual development of personality changes characteristic of epilepsy and (or ) characteristic epileptic dementia. In some cases, epileptic psychoses are also observed, which occur acutely or chronically and are manifested by such affective disorders as fear, melancholy, aggressiveness or an increased ecstatic mood, as well as delusions, hallucinations. If the occurrence of epileptic seizures has a proven connection with somatic pathology, then we are talking about symptomatic epilepsy. In addition, within the framework of epilepsy, the so-called temporal lobe epilepsy is often distinguished, in which the convulsive focus is localized in the temporal lobe. This allocation is determined by the peculiarities of clinical manifestations characteristic of the localization of the convulsive focus in the temporal lobe of the brain. Neurologists and epileptologists are involved in the diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy.

In some cases, seizures complicate the course of a neurological or somatic disease or brain injury.

Causes

Modern research shows that such epilepsy occurs due to congenital (idiopathic) anomalies. The main reason for the development of pathology is a violation of the maturation of the cortex in a child in the temporal region of the brain.

However, idiopathic factors of another type cannot be excluded. Benign epilepsy of childhood in approximately 20-60% of cases is caused by genetic disorders that are inherited.

In addition, researchers identify the following factors that increase the risk of rolandic epilepsy:

- gestosis during pregnancy;

- traumatic brain injuries;

- frequent overwork;

- insufficient sleep duration;

- infectious lesion of the central nervous system.

The benign form of epilepsy is one of the age-dependent pathologies.

The frequency and intensity of relapses decrease as the child gets older. This is explained by the fact that over time, the activity of pathological foci in the brain that causes epileptic seizures decreases.

Attitude to epilepsy

The ancient Greeks and Romans explained epilepsy by divine intervention - “Hercules disease”, “divine disease”, “epileptic disease”[3]. Also, one of the medieval manuals for summoning spirits says that if improperly prepared for the ritual, the magician can die, experiencing an epileptic and apoplectic stroke[3].

Society's attitude towards people suffering from epilepsy is ambiguous and mostly negative[4]. People with epilepsy continue to be widely stigmatized. This can affect people economically, socially and culturally.

Classification of attacks

Epileptic seizures can have different manifestations depending on the etiology, localization of the lesion, and EEG characteristics of the level of maturity of the nervous system at the time of the attack. Numerous classifications are based on these and other characteristics. However, from a practical point of view, it makes sense to distinguish two categories:

Primary generalized seizures

Primary generalized seizures are bilaterally symmetrical, without focal manifestations at the time of occurrence. These include two types:

- tonic-clonic seizures (grand mal)

- absence seizures (petit mal) are short periods of loss of consciousness.

Partial seizures

Partial or focal seizures are the most common manifestation of epilepsy. They arise when nerve cells are damaged in a specific area of one of the brain hemispheres and are divided into simple partial, complex partial and secondary generalized.

- simple - during such attacks there is no impairment of consciousness

- complex - attacks with a disturbance or change in consciousness, caused by areas of overexcitation of various localizations and often become generalized.

- secondary generalized seizures - typically begin in the form of a convulsive or non-convulsive partial seizure or absence seizure, followed by a bilateral spread of convulsive motor activity to all muscle groups.

Disease Prevention

There is no primary prevention of pathology.

To prevent seizures, there are a number of recommendations:

- Provide the child with a constant daily routine with sufficient time for rest. One of the reasons for the development of an epileptic seizure is sleep disturbance in the form of short duration.

- The patient should sleep in a room shared with his parents, as it is undesirable to leave him alone. If this is not possible, a baby monitor should be used. Parents who are close to the child can promptly notice the aura and provide the necessary first aid.

- 1-2 hours before bedtime, it is necessary to exclude games on the computer, smartphone, as well as any load that stimulates the brain. In addition, children should not be fed heavily before bed.

Epileptic seizure

The occurrence of an epileptic attack depends on a combination of two factors in the brain itself: the activity of the seizure focus (sometimes also called epileptic) and the general convulsive readiness of the brain. Sometimes an epileptic attack is preceded by an aura (a Greek word meaning “breeze” or “breeze”). The manifestations of the aura are very diverse and depend on the location of the part of the brain whose function is impaired (that is, on the localization of the epileptic focus). Also, certain conditions of the body can be a provoking factor for an epileptic attack (epileptic attacks associated with the onset of menstruation; epileptic attacks that occur only during sleep). In addition, an epileptic seizure can be triggered by a number of environmental factors (for example, flickering light). There are a number of classifications of characteristic epileptic seizures. From a treatment point of view, the most convenient classification is based on the symptoms of attacks. It also helps to distinguish epilepsy from other paroxysmal conditions.

International Classification of Epileptic Seizures (ILAE, 1981)

- Partial (focal, local) seizures. Simple partial seizures occurring without impairment of consciousness. Motor seizures:

- focal motor without march;

- focal motor with march (Jacksonian);

- adversive;

- postural;

- phonatory (vocalization or stopping speech).

- Somatosensory seizures or seizures with special sensory symptoms (simple hallucinations, eg flashes of flame, ringing):

- somatosensory;

- visual;

- auditory;

- olfactory;

- taste;

- with dizziness.

- Attacks with vegetative-visceral manifestations (accompanied by epigastric sensations, sweating, redness of the face, constriction and dilation of the pupils).

- Seizures with mental dysfunction (changes in higher nervous activity); rarely occur without impairment of consciousness, more often they manifest themselves as complex partial seizures:

- dysphasic;

- dysmnestic (for example, a feeling of “already seen”);

- with impaired thinking (for example, daydreaming, impaired sense of time);

- affective (fear, anger, etc.);

- illusory (for example, macropsia);

- complex hallucinatory (for example, music, scenes, etc.).

- Simple partial seizure followed by loss of consciousness:

- begins with a simple partial seizure (A.1 - A.4) followed by impaired consciousness;

- only with impaired consciousness;

- Simple partial seizures (A), turning into complex and then generalized.

- Absence seizures Typical absence seizures

- only with impaired consciousness;

- changes in tone are more pronounced than with typical absence seizures;

- random attacks that occur unexpectedly and for no apparent reason;

International Classification of Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes (1989)

- LOCALIZATION-DETERMINED (FOCAL, PARTIAL) EPILEPSY AND SYNDROMES Idiopathic (with age-dependent onset) Benign epilepsy of childhood with central temporal peaks

- Epilepsy of childhood with occipital paroxysms

- Primary reading epilepsy

- Chronic progressive permanent epilepsy of childhood (Kozhevnikov syndrome)

- Idiopathic (with age-dependent onset) Benign familial neonatal seizures

- Nonspecific etiology Early myoclonic encephalopathy

- With generalized and focal seizures Neonatal seizures

- Situation-related seizures Febrile seizures

Forms of the disease in children

There are several forms of epilepsy in children.

Benign local epilepsy

Otherwise called Rolandic epilepsy, it is manifested by pharyngeal-oral and unilateral facial motor seizures that occur during falling asleep and waking up. This is a common type of paroxysm in children. The disease manifests itself in childhood from 2 to 14 years. Mostly boys are affected.

It is characterized by simple partial paroxysms that appear during falling asleep and waking up. It all starts with paresthesia, loss of sensitivity in the oropharynx, gums, and tongue.

Then the children make sounds like when gargling, a large amount of saliva is released. Twitching of the facial muscles appears: clonic, tonic and clonic-tonic convulsions of the muscles of the mouth, pharynx, and facial muscles. In some patients, the cramps spread to an arm or leg. Attacks can develop into generalized paroxysms.

Benign myoclonic epilepsy of newborns

These are generalized paroxysms in the form of myoclonic convulsions. It begins between the age of three months and the age of four years. It is manifested by nodding movements of the head and lifting of the torso and shoulders, movements of the elbows to the sides. Consciousness is preserved, attacks gradually become more frequent. In such children, muscle tone is reduced, the psyche develops normally.

Doose syndrome

Doose syndrome - myoclonic-astatic paroxysms. It begins in children from one year of age to 5 years. Manifested by asynchronous contraction of the muscles of the limbs. The attacks are short-lived. Nodding movements with lifting of the body may appear. Consciousness is preserved.

Seizures occur frequently, sometimes several per minute, called status epilepticus.

In such children, coordination of movements is impaired, the central nervous system is affected, and they are lagging behind in mental development.

Childhood and juvenile absence seizure

Juvenile and childhood absence seizures are generalized seizures lasting several seconds, with absence, freezing, and a small number of motor contractions.

Rare forms of the disease

Panagiotopoulos syndrome is a benign childhood idiopathic partial epilepsy with occipital seizures and early onset between 1 and 13 years of age. Attacks in this form are severe.

Characterized by autonomic disorders and a long absence of consciousness, they occur during sleep: first vomiting, then the head and eyes turn in one direction. Paroxysms become generalized. Attacks occur rarely, 1-2 times throughout the entire medical history.

Gastaut syndrome is a benign epileptic syndrome with occipital seizures and late onset between the ages of three and 15 years. The attacks are simple, lasting from several seconds to several minutes, during which visual hallucinations occur. After the attack, patients experience severe headache with nausea and vomiting.

Convulsive focus

A seizure focus is the result of organic or functional damage to an area of the brain caused by any factor (insufficient blood circulation (ischemia), perinatal complications, head injuries, somatic or infectious diseases, tumors and abnormalities of the brain, metabolic disorders, stroke, toxic effects of various substances). At the site of structural damage, a scar (which sometimes forms a fluid-filled cavity (cyst)). In this place, acute swelling and irritation of the nerve cells of the motor zone may periodically occur, which leads to convulsive contractions of skeletal muscles, which, in the case of generalization of excitation to the entire cerebral cortex, result in loss of consciousness.

Convulsive readiness

Convulsive readiness is the probability of an increase in pathological (epileptiform) excitation in the cerebral cortex above the level (threshold) at which the anticonvulsant system of the brain functions. It can be high or low. With high convulsive readiness, even slight activity in the focus can lead to the appearance of a full-blown convulsive attack. The convulsive readiness of the brain can be so great that it leads to a short-term loss of consciousness even in the absence of a focus of epileptic activity. In this case we are talking about absence seizures. Conversely, convulsive readiness may be absent altogether, and, in this case, even with a very strong focus of epileptic activity, partial seizures occur that are not accompanied by loss of consciousness. The cause of increased convulsive readiness is intrauterine brain hypoxia, hypoxia during childbirth, or hereditary predisposition (the risk of epilepsy in the offspring of patients with epilepsy is 3-4%, which is 2-4 times higher than in the general population).

Lifestyle and Cautions

In order to improve the patient's condition, it is necessary to adhere to the diet prescribed by the doctor. As a rule, it does not differ from diets prescribed to people with other forms of epilepsy.

Some doctors exclude liquid from the patient's diet, while other doctors prescribe a protein-free or salt-free diet. Without fail, the patient will have to give up the following:

- alcohol;

- coffee;

- tea;

- smoking.

The doctor may also prescribe a ketogenic diet, which is aimed at reducing attacks. It is worth starting with fasting, that is, you can only drink still water. Starting from the fourth day, it is allowed to introduce some foods into food. The food you eat should contain a lot of fat.

As a rule, people who have been diagnosed with this disease are considered disabled, since they have certain restrictions in relation to work.

So, people with this diagnosis cannot work with the following equipment and in the following areas:

- with computing devices;

- on conveyor lines;

- with water, chemicals;

- with foci of inflammation and fire;

- in enterprises with low or high temperatures.

To ensure that a sick person does not harm his health, he must adhere to the following recommendations:

- limit the use of sharp objects;

- drive a car only in the presence of other people;

- vacation in a sanatorium every year;

- visit swimming pools, ponds, rivers in the presence of others;

- walk in the fresh air and exercise every day.

Diagnosis of epilepsy

Electroencephalography

For the diagnosis of epilepsy and its manifestations, the method of electroencephalography (EEG), that is, the interpretation of the electroencephalogram, has become widespread. Particularly important is the presence of focal peak-wave complexes or asymmetric slow waves, indicating the presence of an epileptic focus and its localization. The presence of high convulsive readiness of the entire brain (and, accordingly, absence seizures) is indicated by generalized peak-wave complexes. However, it should always be remembered that the EEG does not reflect the presence of a diagnosis of epilepsy, but the functional state of the brain (active wakefulness, passive wakefulness, sleep and sleep phases) and can be normal even with frequent attacks. Conversely, the presence of epileptiform changes on the EEG does not always indicate epilepsy, but in some cases it is the basis for prescribing anticonvulsant therapy even without obvious seizures (epileptiform encephalopathies).

Establishing diagnosis

Early diagnosis is very important in the study of epilepsy. In addition, for a quick recovery of the patient, it must be accurate. The first thing you need to start with is identifying the reasons why the attack occurred. Treatment will depend on the causes of the disease.

One of the important methods in diagnosis is electroencephalography, thanks to which it is possible to identify electrical potentials between two points. To carry out this procedure, you need to put electrodes on your head. This method allows you to identify the focus of inflammation, the characteristics of waves and changes in the condition of a sick person in the period between attacks.

In addition, the patient should be examined by a neurologist, who after the examination can draw the following conclusions:

- How pronounced are the patient’s reflexes;

- are there any deviations in the emotional and intellectual spheres;

- Is the patient's condition normal?

Auxiliary methods for confirming the diagnosis include the following:

- MRI;

- CT;

- Echo-encephalogram;

- Antiography of cerebral vessels.

Cause of death in epilepsy

Status epilepticus is especially dangerous due to pronounced muscle activity: tonic-clonic convulsions of the respiratory muscles, aspiration of saliva and blood from the oral cavity, as well as delays and arrhythmias of breathing lead to hypoxia and acidosis; the cardiovascular system experiences extreme stress due to enormous muscular work; hypoxia increases cerebral edema; acidosis increases hemodynamic and microcirculation disorders; secondly, the conditions for brain function are increasingly deteriorating. With prolonged epistatus in the clinic, the depth of the comatose state increases, convulsions become tonic in nature, muscle hypotonia is replaced by atony, and hyperreflexia is replaced by areflexia. Hemodynamic and respiratory disorders increase. The convulsions may stop completely, and the stage of epileptic prostration begins: the eye slits and mouth are half-open, the gaze is indifferent, the pupils are wide. In this condition, death can occur. Two main mechanisms lead to cytotoxicity and necrosis, in which cellular depolarization is supported by stimulation of NMDA receptors and the key point is the initiation of a cascade of destruction within the cell. In the first case, excessive neuronal excitation results from edema (fluid and cations entering the cell), leading to osmotic damage and cell lysis. In the second case, activation of NMDA receptors activates the flow of calcium into the neuron with the accumulation of intracellular calcium to a level higher than that accommodated by the cytoplasmic calcium-binding protein. Free intracellular calcium is toxic to the neuron and leads to a series of neurochemical reactions, including mitochondrial dysfunction, activates proteolysis and lipolysis, which destroy the cell. This vicious circle underlies the death of a patient with epistatus.

The most common cause of death in epilepsy is drowning in the bathtub during an epileptic seizure. For this reason, approximately 1 death per year per 1000 patients occurs.

Prognosis for epilepsy

In the 19th century, there was a widespread belief that epilepsy caused an inevitable decline in intelligence. In the 20th century, this idea was revised: it was discovered that cognitive decline occurs only in relatively rare cases[5]:287.

In most cases, after a single attack, the prognosis is favorable. Approximately 70% of patients undergo remission during treatment, that is, they are seizure-free for 5 years. In 20-30%, seizures continue; in such cases, simultaneous administration of several anticonvulsants is often required.

Living with epilepsy

Contrary to popular belief that a person with epilepsy will have to limit himself in many ways, that many roads in front of him are closed, life with epilepsy is not so strict. The patient himself, his loved ones and those around him need to remember that in most cases they do not even need to register a disability. The key to a full life without restrictions is the regular, uninterrupted use of medications selected by a doctor. The brain, protected by drugs, becomes less susceptible to provoking influences. Therefore, the patient can lead an active lifestyle, work (including on the computer), do fitness, watch TV, fly airplanes and much more.

But there are a number of activities that are essentially a “red rag” for the brain of a patient with epilepsy. Such actions should be limited:

- Car driving;

- Working with automated mechanisms;

- Swimming in open water, swimming in a pool without supervision;

- Self-cancellation or skipping pills.

There are also factors that can cause an epileptic attack even in a healthy person, and they should also be wary of:

- Lack of sleep, night shift work, 24-hour work schedule.

- Chronic use or abuse of alcohol and drugs

Epilepsy and personality

In the 19th century, authors of works on psychiatry suggested that epileptic seizures cause personality destruction. At the beginning of the 20th century, the opinion was established that both epilepsy and personality changes associated with this disease are a consequence of some general underlying pathology. A common view was that the “epileptic personality” was characterized as self-centered, irritable, religious, quarrelsome, stubborn, and viscous-minded. Later it became obvious that these ideas arose as a result of observations of seriously ill patients with serious brain damage constantly staying within the walls of clinics. A survey of patients with epilepsy living in the community has led to the conclusion that only a minority of them experience difficulties due to personality anomalies, and when such personality problems do arise, they are usually not of any specific nature. In particular, there is very little evidence to support the hypothesis of a link between epilepsy and aggression[5]:287.

In cases where a patient with epilepsy does have a personality disorder, social factors appear to play an important role in its etiology - in particular, social restrictions imposed on the epileptic, his own difficulties, and the reactions of others. It has also been suggested that personality pathology in epilepsy may be associated with damage to the temporal lobe of the brain[5]:287.

Diet and patient status

In the presence of epilepsy, which is accompanied by loss of adequacy, a person is assigned a disability group. He should not perform work associated with an increased level of control and concentration, as this can provoke a lot of adverse consequences.

It is also advisable to avoid driving a vehicle.

It is important for relatives to constantly monitor the patient, and also to limit the number of piercing and cutting objects that can be traumatic when an attack occurs.

It is recommended to undergo special rehabilitation courses, where an experienced doctor will tell you what the patient’s lifestyle should be.

The consumption of alcoholic beverages and smoking should be completely avoided. Limit fatty and fried foods, and carefully monitor your diet.

People suffering from epilepsy do not pose a danger to society, however, in some situations, when a person cannot control his behavior, his stay in a group should be carried out exclusively under the supervision of someone close to him who can provide first aid if necessary.

Thus, idiopathic epilepsy has several forms that differ from each other in the clinical picture of the attack. Early diagnosis and comprehensive treatment, as well as constant monitoring of health status, will reduce the frequency and intensity of attacks, but it is impossible to completely get rid of the disease.

Many people, seeing a person on the street or in transport who is having an epileptic seizure, do not know how to help. First aid for epilepsy is a set of simple measures that can be carried out by anyone without medical education.

Based on what symptoms a child is diagnosed with epilepsy, we will tell you in this topic.

Treatment of epilepsy

The overall treatment goal can be divided into individual goals that require different efforts:

Treatment goals for epilepsy

| Goal name | Ways to achieve |

| Pain relief during attacks | For patients experiencing pain during an attack, reduce it, for example, by regularly taking anticonvulsant and/or painkillers. In addition to medications, other remedies may also be suitable. For example, regular consumption of calcium-rich dried prunes can help relieve pain in this case, but this method does not eliminate the cause of seizures - the spontaneous reaction of the onset of an attack in the brain of a patient with epilepsy; it will only increase the calcium content in the body, which may alleviate the course of seizures. |

| Prevent the onset of new attacks | Surgical, medical, Ketogenic diet |

| Reduce the frequency of attacks | If attacks cannot be completely prevented, the goal of reducing their frequency may be achieved. Surgical, medical, VNS therapy, Ketogenic diet |

| Reduce the duration of individual attacks | Seizures with breath holding that last more than a minute are called severe seizures, and those that last less than 10-15 seconds are called mild ones. During severe breath-holding attacks, the brain and other organs may be damaged due to a lack of oxygen supply. |

| Achieve drug withdrawal | No recurrence of seizures |

| Minimize side effects of treatment | Selected individually |

| To protect society from patients with epilepsy who commit socially dangerous actions | In anticipation of an attack, during it or after it, patients may feel in a special way, which can lead to an insane state and the commission of illegal actions. Medication, physical restraint: isolation, putting on a straitjacket; preventive measures - for example, in the form of regular monitoring to ensure that the fingernails are trimmed and in a deranged state it will be impossible to scratch other people with them. |

Treatment of the disease is carried out both on an outpatient basis (with a neurologist or psychiatrist) and inpatiently[4] (in neurological hospitals and departments or in psychiatric departments - in the latter, in particular, if a patient with epilepsy has committed socially dangerous actions in a temporary mental disorder activities or chronic mental disorders and compulsory medical measures were applied to him)[6]. In the Russian Federation, compulsory hospitalization must be authorized by a court. In especially severe cases, this is possible before the judge makes a decision [ source not specified 691 days

]. Patients forcibly placed in a psychiatric hospital are recognized as incapable of work for the entire period of their stay in the hospital and have the right to receive a pension and benefits in accordance with the legislation of the Russian Federation on compulsory social insurance[7].

Drug treatment of epilepsy

- Anticonvulsants, also known as anticonvulsants, reduce the frequency, duration, and in some cases completely prevent seizures.

Epilepsy is treated primarily with anticonvulsants, which may continue to be used throughout a person's life.[8] The choice of anticonvulsant depends on the type of seizures, epilepsy syndromes, health status and other medications taken by the patient.[9] In the beginning, it is recommended to use one product.[10] If this does not have the desired effect, it is recommended to switch to another medicine.[11] Take two drugs at the same time only if one does not work.[11] In approximately half of the cases, the first remedy is effective, the second is effective in another 13%. The third or a combination of two can help an additional 4%.[12] About 30% of people continue to have seizures despite treatment with anticonvulsants.[13]

Possible drugs include phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproic acid, and are approximately equally effective for both partial and generalized seizures (absences, clonic seizures).[14][15] In the UK, carbamazepine and lamotrigine are recommended as first-line drugs for the treatment of partial seizures, and levetiracetam and valproic acid as second-line drugs due to their cost and side effects.[11] Valproic acid is recommended as first-line treatment for generalized seizures, and lamotrigine second.[11] For those who are seizure-free, ethosuximide or valproic acid are recommended, which are particularly effective for myoclonic and tonic or atonic seizures.[11]

In April 2020, an FDA advisory panel recommended the registration of a cannabidiol-based drug. Its purpose is the treatment of severe forms of epilepsy in children. If the regulator's decision is positive, the drug will become the first registered medical marijuana product in the United States. The drug is presented in the form of syrup, the content of tetrahydrocannabinol is less than 0.1%. The drug has successfully passed clinical trials among children over 2 years of age suffering from Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome - rare and severe forms of epilepsy. According to trial data, a cannabidiol-based drug helps reduce the frequency of attacks by 50% in 40% of patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (in the placebo group the figure is 15% of patients). Similar effectiveness has been demonstrated in the treatment of Dravet syndrome.[16]

- Neurotropic drugs - can inhibit or stimulate the transmission of nervous excitation in various parts of the (central) nervous system.

- Psychoactive substances and psychotropic drugs affect the functioning of the central nervous system, leading to changes in mental state.

- Racetams are a promising subclass of psychoactive nootropic substances.

Non-drug treatments

- Ketogenic diet

- Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve

- Surgery

- Voight method

- Studying the influence of external stimuli that influence the frequency of attacks and weakening their influence. For example, the frequency of attacks may be influenced by the daily routine, and it may be possible to establish a connection individually, for example, when wine is consumed and then washed down with coffee, but this is all individual for each patient with epilepsy[ source not specified 688 days

][

style

] .

Treatment

There is no consensus on whether or not to treat benign epilepsy in childhood. This is due to the fact that even without medication or other intervention, complete remission occurs. However, some researchers note that if therapy is not carried out in children, then over time, rolandic epilepsy provokes the development of pseudo-Lennox syndrome, or an atypical form of the disease.

In addition, it is not always possible to make an accurate diagnosis. And if seizures are caused by another disease, then in the absence of adequate treatment, severe complications may develop.

In connection with the above, treatment tactics are selected on an individual basis. If the doctor decides to start therapy, the patient is prescribed one of the valporic acid drugs. Antiepileptic drugs such as Carbamazepine or Diphenine are also used in the treatment of the disease (recommended for children over 7 years of age). Moreover, if attacks occur only at night, then a single dose of medication is prescribed before going to bed.

To reduce relapse rates, children should get adequate rest. It is important to maintain a sleep-wake schedule. It is not recommended to feed the patient heavily before going to bed.

If positive results of antiepileptic therapy are achieved, the child is transferred to a specialized diet, which includes foods high in fat.

Notes

- Commission on Epidemiology and Prognosis, International League Against Epilepsy (1993). “Guidelines for epidemiologic studies on epilepsy. Commission on Epidemiology and Prognosis, International League Against Epilepsy.” Epilepsia 34

(4):592–6. DOI:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb00433.x. PMID 8330566. - Blume W, Lüders H, Mizrahi E, Tassinari C, van Emde Boas W, Engel J (2001). "Glossary of descriptive terminology for ictal semiology: report of the ILAE task force on classification and terminology." Epilepsia 42

(9):1212–8. DOI:10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.22001.x. PMID 11580774. - ↑ 12

Epilepsy. Diseases in history - ↑ 1 2 Kazennykh T.V., Semke V.Ya.

Psychotherapeutic correction in the system of complex therapy of patients with epilepsy // Siberian Scientific Medical Journal. - 2006. - No. 1. - ↑ 1 2 3 Gelder M., Gat D., Mayo R.

Oxford Manual of Psychiatry: Trans. from English - Kyiv: Sfera, 1999. - T. 1. - 300 p. — 1000 copies. — ISBN 966-7267-70-9, 966-7267-73-3. - A.V.

Shpak, I.A. Basinskaya. Compulsory treatment of patients with epilepsy (Russian). Retrieved December 27, 2010. Archived February 4, 2012. - Law of the Russian Federation “On psychiatric care and guarantees of the rights of citizens during its provision” dated No. 3185-I (July 2, 1992), Article 13.

- National Clinical Guideline Center.

The Epilepsies: The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. — National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, January 2012. — P. 21–28. - National Clinical Guideline Center.

The Epilepsies: The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. — National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, January 2012. - Elaine Wyllie.

Wyllie's Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice. - Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012. - P. 187. - ISBN 978-1-4511-5348-4. - ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 National Clinical Guideline Center.

The Epilepsies: The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. - National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, January 2012. - P. 57–83. - Medical aspects of disability; a handbook for the rehabilitation professional. — 4th. - New York: Springer, 2010. - P. 182. - ISBN 978-0-8261-2784-6.

- (Nov 2011) “Genetics of epilepsy.” Semin Neurol 31

(5):506–18. DOI:10.1055/s-0031-1299789. - Nolan, S. J. (23 August 2013). "Phenytoin versus valproate monotherapy for partial onset seizures and generalized onset tonic-clonic seizures." The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 8

: CD001769. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001769.pub2. PMID 23970302. - Tudur Smith, C (2002). "Carbamazepine versus phenytoin monotherapy for epilepsy." The Cochrane database of systematic reviews

(2): CD001911. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD001911. PMID 12076427. - The first drug with cannabidiol is preparing to enter the US market

Literature

- Bryukhanova N. O., Zhilina S. S., Ayvazyan S. O., Ananyeva T. V., Belenikin M. S., Kozhanova T. V., Meshcheryakova T. I., Zinchenko R. A., Mutovin G. R., Zavadenko N.N.

Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome in children with idiopathic epilepsy // Russian Bulletin of Perinatology and Pediatrics. — 2020. — No. 2. — P. 68–75. — ISSN 1027-4065. - Bryukhanova N. O., Zhilina S. S., Belenikin M. S., Mutovin G. R., Ayvazyan S. A., Prityko A. G.

Possibilities of genetic testing for resistant forms of epilepsy // Pediatrics. Journal named after G. N. Speransky. — 2020. — No. 5. — P. 77–80. — ISSN 0031-403X. - Abramov A. A., Shakhtarin V. V., Ayvazyan S. O., Zhilina S. S., Osipova K. V., Yavorskaya M. M., Bachmanova M. S., Mutovin G. R., Prityko A. G.

Polymorphism of the MDR1 gene and pharmacoresistance to anticonvulsants in epilepsy // Children's Hospital. - 2011. - No. 4. - P. 12-15. — ISSN 2076-3875. - Ayvazyan S. O., Shiryaev Yu. S.

Video-EEG monitoring in the diagnosis of epilepsy in children // Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. - 2010. - No. 6. - P. 70–76. — ISSN 1997-7298. - Victor M., Ropper A.H.

Guide to neurology according to Adams and Victor: textbook. manual for the postgraduate system. prof. physician education / Maurice Victor, Allan H. Ropper; scientific ed. V. A. Parfenov; lane from English edited by N. N. Yakhno. — 7th ed. - M.: Med. information agency, 2006. - 677 p. — ISBN 5-89481-275-5 - Rosenbach P. Ya.

Epilepsy // Encyclopedic Dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron: in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additional). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

Diagnosis of the disease

Diagnosing rolandic epilepsy in children without the participation of a doctor is quite difficult. The active stage of the disease is not always accompanied by muscle cramps. In addition, the pathology usually manifests itself before, during or immediately after sleep, and the attacks are short-term in nature, which is why parents do not notice deviations in the child’s development.

The basis for diagnosing the disease is encephalography, which shows the abnormal activity of individual areas (sections) of the brain.

The procedure is informative only if it is carried out during an attack. In this regard, if epilepsy is suspected, polysomnography or EEG monitoring is prescribed.

If necessary, diagnostic measures are supplemented by MRI and CT scan of the brain. These procedures make it possible to determine organic damage to the organ and other disorders that cause symptoms similar to epileptic seizures. If damage is detected in the structures of the brain, additional studies will be required, the results of which can identify or exclude a relationship between seizures and organic damage to nerve tissue.