Mental disorders in epilepsy

3. Mental disorders in epilepsy. There are paroxysmal and permanent disorders.

3.1. Paroxysmal mental disorders in epilepsy. In addition to the mental seizures described above with a duration of up to 10 minutes, i.e. simple partial sensory seizures, simple partial seizures with mental disorders, as well as complex partial seizures with mental disorders in the form of a seizure aura, transient (transitory) mental disorders are also distinguished: dysphoria , twilight stupefaction, epileptic psychoses. Their duration ranges from several hours to a day.

1) Dysphoria. The most common form of mental disorder is epilepsy. Dysphoria is an autochthonous mood disorder that combines sadness, anger, and fear. Depending on the structure of affect, the following clinical variants of dysphoria are distinguished:

- explosive dysphoria. It is distinguished by an extreme degree of emotional stress, affective excitability to the point of rage, rage and aggressiveness, and a tendency to destructive actions. Homocidal and/or suicidal tendencies are often observed;

- anxious (anxious) dysphoria. Typical states of horror are close to a panic attack, fear (of death, insanity, brain stroke, etc.). In addition, tachycardia, respiratory failure, dizziness, tremor, dry mouth, hyperhidrosis, feelings of heat or cold, urge to urinate, defecate, etc. are noted;

- melancholic (sad) dysphoria. A depressed mood with a melancholy affect, motor retardation, difficulty concentrating, and ideational inhibition with loss of the ability to understand and evaluate what is happening predominate.

Rarely, but there are states with an uplift in mood with cheerfulness, enthusiasm, ecstasy, or Mori-like states (euphoria with foolishness, disinhibition, a tendency to inappropriate jokes and ridiculous antics).

2) Twilight stupefaction. Characterized by deep confusion of consciousness with preservation of the ability to outwardly purposeful, consistent behavior.

General characteristics of clouding of consciousness, according to K. Jaspers (1911):

- detachment from the surrounding reality;

- disorientation in time, location, situation, and often in one’s own personality;

- inconsistency, fragmentation of thinking;

- Congrade amnesia for the period of confusion, complete, partial, sometimes delayed.

Twilight stupefaction is also characterized by:

- acute, sudden onset;

- relative short duration (lasts for several hours);

- the presence of affective disorders: fear, melancholy and anger are typical;

- interruption of meaningful contact with others, loss of the ability to understand what is happening, mutism (no speech or individual words, phrases are pronounced, there is no understanding of the speech of others);

- disorientation, primarily in one’s own personality, which is presumably manifested by a loss of the ability to perceive one’s own prosocial qualities and be guided by them, i.e., internalized or accepted norms of social behavior. Behavior is determined by affective disorders, deceptions of perception, delusions, which represent a psychotically altered personality, towards which there is no critical attitude;

- predominantly visual hallucinations, acute sensory delirium of persecutory content;

- outwardly ordered aggressive behavior with homocidal or, less commonly, suicidal tendencies or chaotic agitation with destructive actions;

- critical ending;

- terminal sleep;

- complete or partial congrade amnesia, which can sometimes be delayed.

In domestic psychiatry, it is customary to distinguish the following clinical variants of twilight stupefaction.

1. Simple form. Characterized by outwardly ordered behavior, actions are in the nature of an automated reaction to immediate impressions (obtained from a narrow range of perceived stimuli, as is typical for an individual in twilight). No delusions, deceptions of perception, or intense affect are noted. Spontaneous speech is absent, as is the reaction to the speech of others.

2. Paranoid form. Acute sensory delirium of persecutory content, pronounced affects of melancholy, anger, and fear are observed. Outwardly, the behavior is also orderly and consistent, but its motivation is exclusively delusional.

3. Delirious form. It is characterized by the predominance of visual illusions of perception, which apparently have a scene-like character, which determines the behavior of patients.

4. Oneiric form. Affective tension is combined with hallucinatory-delusional experiences of fantastic content, as well as psychomotor retardation, sometimes reaching the level of stupor. The memory of experiences during psychosis is partially preserved; usually these are psychotic impressions; what happened in the surrounding reality is not recorded in memory.

5. Dysphoric form. It is characterized by intense affects of melancholy and anger, rage, frantic excitement, impulsive actions of a homocidal, destructive, suicidal nature.

6. Oriented version of twilight stupefaction. The main feature of the disorder is a relatively shallow degree of clouding of consciousness, in which the patient retains the ability to generally orient himself in the environment and in time, to recognize acquaintances, especially people close to him. In this case, for a short time, pronounced affects of melancholy and anger, persecutory delusions and hallucinations of threatening content may appear, and therefore corresponding behavioral disorders arise. Congrade amnesia is partial and sometimes delayed (retarded, occurring 1–2 hours after the end of psychosis). The patient’s appearance helps to recognize the twilight state: he gives the impression of a slightly lethargic, not fully awake person, he moves with an uncertain, unsteady gait, his speech is slow and somewhat blurred. There are a number of gradations and transitions between dysphoria and an oriented twilight state, so distinguishing between these two disorders can be quite difficult.

3.2. Epileptic psychoses. Depending on the time of occurrence in relation to seizures, ictal, postictal and interictal psychoses are distinguished, by the nature of the onset - latent and acute psychoses, by the state of consciousness - from psychoses with clear consciousness to psychoses with severe confusion, by duration - short-term and chronic, by reactions to treatment – curable and resistant to therapy.

1) Ictal (Latin ictus - blow, stress) psychoses - usually these are simple partial mental and complex partial seizures with mental disorders. With the status of such seizures, i.e. non-convulsive status epilepticus, the clinical picture of the disease state includes a variety of affective and behavioral disorders, perceptual disorders (illusions, hallucinations), psychomotor automatisms, and with the status of complex partial seizures with mental disorders, confusion of consciousness is always noted ( During the status of simple partial mental seizures, consciousness may remain clear or stupefaction is limited to a mild degree). At the end of the status, which occurred with impaired consciousness, congrade amnesia, total or fragmentary, is revealed.

Status epilepticus with schizophrenia-like symptoms (verbal hallucinations, pseudohallucinations, persecutory delusions) is usually characterized by hyperkinesis, in particular eyelid myoclonus, as well as oral automatisms.

2) Postictal psychoses. As a rule, they complicate drug-resistant epilepsy. Occur after a series of seizures, focal or tonic-clonic. Stupefaction develops with acute polymorphic delirium and affective disorders. Psychosis lasts up to 1–2 weeks. There are 2 types of psychosis:

- a prolonged twilight state of consciousness. It occurs after a series of tonic-clonic seizures and lasts for several days. Stupefaction is combined with hallucinations, delusions, intense affect, motor agitation, and aggression;

- epileptic oneiroid. It occurs suddenly (how it differs from schizophrenic oneiroid). Against the background of affective disorders (ecstasy, delight, anger, horror), fantastic illusions, visual and auditory hallucinations, and an influx of vivid dream-like ideas appear. A typical violation of autopsychic orientation is: patients “reincarnate” into characters from fairy tales, legends, inhabitants of the other world, space aliens, etc. In this case, catatonic substupor or agitation is observed.

3) Short-term interictal psychoses. Occur during a period of decreased frequency of seizures or their cessation in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. As a rule, this occurs more than 15 years after the onset of epilepsy. The clinical picture of psychoses is polymorphic and usually includes affective disorders, hallucinatory-paranoid syndrome, paraphrenic and catatonic syndromes, occurring against the background of clear consciousness. In connection with such psychoses, at one time a hypothesis was put forward about the existence of schizoepilepsy (a combination of schizophrenia and epilepsy), which is now half-forgotten. The following variants of transient interictal psychoses are distinguished:

- acute epileptic psychoses without stupefaction: a) acute paranoid. It manifests itself as a primary acute sensory delusion, which is combined with illusions, acoustic, optical and other deceptions of perception of frightening content, psychotic behavior in which destructive and aggressive actions predominate. The state can change to anxious-fearful with passive aggressiveness (flight from imaginary pursuers); b) acute affective psychoses. These are psychoses in which a tense dysphoric state and behavioral disorders predominate, reflecting the predominance of one or another affective radical of dysphoria (fear, melancholy or anger);

- Landolt syndrome. Occurs in 8% of patients with interictal psychoses. It is characterized by hallucinatory-delusional psychosis lasting from several days to a number of weeks. During this period, epileptic seizures are reduced or disappear, while the EEG is “forcibly” normalized. It is believed that the factors provoking the development of this syndrome are anticonvulsant therapy (using barbiturates, benzodiazepines, succinimides), as well as polypharmacy using high doses of topiromate. The prognosis is relatively favorable.

4) Chronic epileptic psychoses (schizoepilepsy, symptomatic schizophrenia, schizophrenia-like epileptic psychoses). There are these forms:

- paranoid epileptic psychoses. They are characterized by a slowly progressive primary systematized delusion of everyday content (delusions of relationship, poisoning, damage, illness, religious obsession, etc.), existing against the background of a melancholy-angry or enthusiastic-ecstatic mood characteristic of epilepsy;

- hallucinatory-paranoid epileptic psychoses. Various manifestations of the syndrome of mental automatism or Kandinsky-Clerambault are observed (delusions of physical and physical influence, sensory, ideational and other automatisms, especially verbal hallucinations and pseudohallucinations, delusions of openness and mastery). For epilepsy, fragmentation, rudimentary and incompleteness of this syndrome, on the one hand, and pathological thoroughness, i.e., excessive detail, in patients’ reports about their psychotic experiences, on the other, are considered typical. Usually the sensory, hallucinatory version of the syndrome predominates. These disorders are combined with anxious-melancholy mood disorder, fears, as well as episodes of clouding of consciousness;

- paraphrenic epileptic psychoses. They are predominantly a hallucinatory variant of paraphrenic syndrome with the presence of verbal hallucinations and pseudohallucinations of megalomaniac content, hallucinatory delusions of fantastic content. Affective disorders are also noted, such as euphoria with complacency, an ecstatically enthusiastic mood. In addition, a kind of epileptic schizophasia is revealed, very reminiscent of the fragmentation of thinking in schizophrenia;

- catatonic epileptic psychoses. They are characterized by a predominance in the clinical picture of catatonic substupor with symptoms of negativism, in which individual signs of catatonic arousal are also noted (grimacing, foolishness, stereotypies of speech, actions and postures, iterations, echolalia, echopraxia, etc.).

These psychoses and seizures can be in different relationships. In some cases, psychosis is accompanied by a reduction or cessation of seizures and forced normalization of the EEG; in other and usually more rare cases, the opposite occurs.

It should be absolutely clear that psychoses in patients with epilepsy (as in other mental illnesses) may have another etiology, for example, arising in connection with intercurrent pathogenic factors: intoxication, neuroinfection, traumatic brain injury, brain tumor or somatic disease. The clinical picture of such psychoses usually contains an epileptic radical (features of emotional response with phenomena of viscosity and explosiveness, coloring of images of visual hallucinations in blue, red, etc.).

3.3. Permanent (permanent) mental disorders in epilepsy. In almost all cases of the disease, persistent changes in personality and character, expressed to one degree or another, are revealed. In the foreground, contrary to previous ideas, personality changes of the psychasthenic type come to the fore (27.9% of patients). The second place is occupied by personality changes of the explosive type (25.8%), the third - by the glishroid type (21.1% - with viscosity, torpidity, sweetness). Hysterical personality changes predominate in 11.1%, paranoid – in 7.3%, schizoid – in 6.8%. In all cases, symptoms of regression are observed, which is manifested by increasing phenomena of egocentrism (decreased ability to share the position of another person, see oneself from the outside, priority of personal opinion, weakening of reflection, etc.).

In addition, there is a slowdown in mental processes, mental torpidity (difficulties in moving from one activity to another), excessive detailing of thinking, a decrease in the ability to remember (especially impressions that do not have personal significance), a narrowing of horizons and range of interests, petty pedantry, importunity , exaggerated cleanliness, ostentatious piety (“God on the lips and a stone in the bosom”). Mental operations (synthesis, generalization, abstraction, etc.) suffer. “Epileptic optimism” is revealed (Khodos H.G., 1974) - an underestimation of the severity of the disease with a loss of critical attitude towards one’s inappropriate behavior, changes in personality and intelligence. Speech and its melody are disrupted. Speech takes on a melodious, drawn-out character, it is slowed down, the vocabulary is shortened, monotonous and diminutive phrases are often used, and a lot of “verbal garbage” appears in speech. In severe cases of the disease, epileptic dementia develops (concentric, visco-apathetic dementia) with apathy, emotional dullness, passivity, “dull resignation to one’s illness.

Do you have any questions? Need some advice? Call us

Return to Contents

Causes

Epilepsy is a disease that can be congenital or acquired. The idiopathic form develops as a result of a hereditary predisposition, the symptomatic form due to primary pathology. The causes of occurrence correlate with the age of the patient:

- In children under 2 years of age. The pathology is caused by congenital anomalies and developmental defects, increased body temperature, birth injuries, and metabolic disorders.

- In children aged 2-14 years. The debut of the idiopathic form occurs more often.

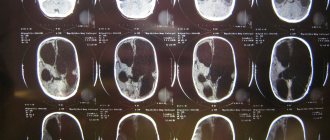

- In adults. Epileptic seizures are caused by injuries in the head area, withdrawal syndrome arising from alcohol addiction, stroke, or a tumor localized in the nervous tissue.

- In the elderly. More often, attacks are associated with tumors that form in the brain and strokes.

Genuine epilepsy, also known as genetic or idiopathic, is associated with congenital malformations - cortical dysplasia (underdevelopment) of the focal (focal) type, holoprosencephaly (absence of the telencephalon hemispheres), lissencephaly (smoothing of the convolutions of the cortical layer of the hemispheres).

Metabolic disorders that correlate with epileptic seizures include peroxisomal diseases (a group of inherited metabolic disorders) and aciduria (a group of inherited diseases characterized by abnormal amino acid metabolism).

Often, the causes of epilepsy are associated with neurodegenerative processes - leukodystrophy (a group of inherited pathologies characterized by damage to the white brain matter), leukoencephalopathy (a progressive, demyelinating disease of the central nervous system of infectious origin), polymicrogyria (the formation of multiple folds in the cortical layer).

In 50% of cases, it is not possible to establish the exact causes of repeated epileptic seizures. The question of whether epilepsy is inherited or not is difficult to answer unambiguously. The important role of hereditary factors (mutations, defective genes) in the pathogenesis of epilepsy has been proven. However, often the presence of gene mutations is not enough for the development of the disease. The leading impetus for the debut of pathology are the following factors:

- Influence of the external environment (unfavorable environmental conditions, intoxication - chronic, acute).

- Psychotraumatic situations.

- Somatic, infectious diseases.

Defective genes cause hidden vulnerability and a person’s susceptibility to disease. However, they are not a prerequisite for its occurrence. Patients with epilepsy often have a family history of relatives who suffered from repeated epileptic seizures.

The likelihood of developing hereditary epilepsy increases if both parents of the child have a similar diagnosis confirmed; this disease is more often transmitted through the female line, however, if there are not a large number of people suffering from the pathology in the family, the risk of the child getting the disease is 1-2%. The disease is less likely to be inherited from the father. More often, the pathology is inherited through the mother.