The material was published in the Neurological Journal. – 2005. – T. 10, No. 4. – P. 37-43.

The problem of damage to the central nervous system after surgery under general anesthesia (GA) is one of the most pressing in neurology and anesthesiology. Such close attention to it is associated, first of all, with the high frequency of anesthetic complications [14;41;42;56;60], the controversial solution to the issue of their preventability, the banality of their causes and damaging ability, the increase (in Western countries) in the number and size of lawsuits for anesthetic errors [1;38;39]. OA can cause various damage to the nervous system in the postoperative period: mental disorders, delirium, convulsive syndrome, opisthotonus, postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), sleep-wake cycle disorders, coordination disorders, choreoathetosis, stroke, acute sensorineural hearing loss, spastic paraplegia , malignant hyperthermia. In this case, dysfunction of the central nervous system varies depending on the type of anesthesia, the state of the somatic and neurological status of the patient in the preoperative period, the age of the patient and many other factors. As a result, it is impossible to conclude that OA causes any specific type of CNS damage. However, most studies devoted to this problem provide data on some general depression of the functional state of the central nervous system in the postoperative period, which is manifested by a decrease in memory, reactivity, attention (postoperative cognitive dysfunction - POCD). It has been noted that virtually all known anesthetics have an adverse effect on cognitive functions. Thus, in modern literature there is evidence of the negative effect on the central nervous system of even moderately therapeutic doses of anesthetics and narcotic analgesics, including: morphine, fentanyl, amphetamine, halothane, sodium oxybutyrate, hexenal, ketamine, Nembutal, propofol (diprivan) [4;6; 11;12]. In recent years, the question of the damaging effects of hypotensive anesthesia on the brain has been raised.

Due to the multifactorial nature of POCD, in recent years there has been a tendency towards a multidisciplinary approach to solving this problem with the involvement of specialists from various specialties, including not only anesthesiologists, but also neurologists, clinical neurophysiologists, pathophysiologists, and medical psychologists [12;33;59].

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction

— POCD is a cognitive disorder that develops in the early and persists in the late postoperative period, clinically manifested in the form of memory impairment, difficulty concentrating (concentrating) attention and impairment of other cognitive (thinking, speech, etc.), confirmed by neuropsychological testing data (decreased testing indicators in the postoperative period by at least 10% of the preoperative level) [49]

.

The severity of POCD in children and adults varies from mild to severe. A number of authors consider OA as a determinant or risk factor for accelerated age-related decline in cognitive functions [47;54;55], but this question currently remains open.

The practical significance of the POCD concept lies in the possibilities of early diagnosis of cognitive disorders and early initiation of neuroprotective treatment [31;51;57;58].

Classification[ | ]

Highlights the lungs

,

moderate

and

severe

cognitive impairment.

Historically, the problems of cognitive disorders have been studied primarily within the framework of the concept of “dementia”: the terms “dementia” and “dementia” mean the most severe cognitive impairment

, leading to maladjustment in everyday life. Only later did much attention begin to be paid to less severe disorders[2].

Mild cognitive impairment

(English: mild cognitive impairment, MCI) are mono- or multifunctional cognitive disorders that clearly go beyond the age norm, but do not limit autonomy and independence, that is, do not cause maladjustment in everyday life. Moderate cognitive impairment, as a rule, is reflected in the individual’s complaints and attracts the attention of others; can interfere with the most complex forms of intellectual activity. The prevalence of moderate cognitive impairment among older people reaches, according to research, 12-17%. Among neurological patients, mild cognitive impairment syndrome occurs in 44% of cases[3].

In accordance with the ICD-10 criteria, a patient complaint must be present

for increased fatigue when performing mental work, decreased memory, attention or learning ability, which does not reach the level of dementia, is based on an organic nature and is not associated with delirium[4].

For mild cognitive impairment

indicators of psychometric scales may remain within the average age norm or deviate slightly from it, but patients are aware of a decrease in cognitive abilities compared to the premorbid level and express concern about this. Mild cognitive impairment is reflected in the patient’s complaints, but does not attract the attention of others; do not cause difficulties in everyday life, even in its most complex forms. Population studies of the prevalence of mild cognitive impairment have not yet been conducted, but it can be assumed that their prevalence is not inferior to the prevalence of moderate cognitive impairment[3].

Clinic and diagnosis of POCD

The most vulnerable to the effects of OA in the field of cognitive functions are the function of attention, short-term memory, and the speed of psychomotor reactions. The presence of emotional disturbances can aggravate the severity of cognitive disorders. The relationship between cognitive and emotional disorders is quite complex. Both types of mental disorders are related by the presence of common pathogenetic factors and are also capable of directly influencing each other. Most researchers point to a combination of POCD and depression. In addition, patients with POCD complain of disturbances in the sleep-wake cycle, rapid fatigue during mental stress, and a decrease in the quality and pace of the usual rhythm of mental and physical activity [33;45;51;53;58;59]. There are isolated descriptions of more severe impairments of cognitive functions, including in young patients: disturbances of consciousness (delayed awakening), amnestic aphasia, agraphia, acalculia, prosopagnosia, etc. [1;6;44;56;60].

For early detection and assessment of the risk of POCD, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), tests for memorizing and reproducing semantic fragments, tests for visual memory, the “5 words” memorization test, and batteries of neuropsychological tests that include research are recommended attention, short-term and long-term memory (auditory and visual), visual-spatial orientation, speech (understanding of syntax, meaning of words, speed of oral and written speech, etc.) [6;16;27;29;44].

In Japan, the Yamaguchi University Mental Disorder Scale (YDS) technique was developed and introduced into clinical practice for diagnosing POCD in elderly patients [40].

In order to clarify the etiology of POCD, laboratory tests of blood gases (arterial and venous), hemoglobin, electrolytes, glucose, serum protein S-100, and neuron-specific enolase (NSE) are recommended. It has been shown that serum protein S-100 may be a significant marker for the development of cognitive impairment in the postoperative period after most non-cardiac surgery, while neuron-specific enolase (NSE) does not reflect postoperative cognitive deficits in general surgical practice [51]. Other authors suggest including in the scope of research: serum osmolarity, creatinine, urea, calcium and magnesium levels in the blood, as well as analyzing the state of liver function. It has been noted that the risk of developing POCD depends more on the severity of acidosis than on alkalosis (moderate acidosis can lead to serious disorders of the central nervous system). Changes in blood osmolarity, hyponatremia or hypernatremia, hypocalcemia or hypercalcemia also increase the risk of developing POCD.

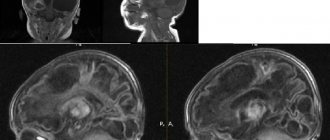

If the etiology of POCD is not clarified according to the above laboratory tests, then one should think about the direct cytotoxic (neurotoxic) effect of individual components of OA on the central nervous system. In order to confirm or exclude the cytotoxicity of anesthetics, the use of drugs such as naloxone, flumazenil, and physostigmine has been proposed. It should be noted that the administration of drugs is recommended to be carried out using the dose titration method, starting with minimal doses and taking into account the response of the patient’s body (and the severity of POCD) to a stepwise increase in the dose of the drug. If a comprehensive analysis of the dynamics of the development of POCD cannot be clarified using the above methods, including a detailed neurological examination, then the scope of the examination includes computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography (PET) of the brain.

Reasons[ | ]

There are several dozen nosological forms within which cognitive impairment develops. These nosological forms include both primary brain diseases and various somatoneurological and mental disorders that negatively affect cognitive functions[2].

The main causes of cognitive impairment may be[2]:

- Neurodegenerative diseases

- Alzheimer's disease

- Dementia with Lewy bodies

- Frontotemporal degeneration (FTD)

- Corticobasal degeneration

- Parkinson's disease

- Progressive supranuclear palsy

- Huntington's chorea

- Other degenerative brain diseases

- Vascular diseases of the brain

- Brain infarction of “strategic” localization

- Multi-infarction condition

- Chronic cerebral ischemia

- Consequences of hemorrhagic brain damage

- Combined vascular lesion of the brain

- Mixed (vascular-degenerative) cognitive impairment

- Dysmetabolic encephalopathies

- Hypoxic

- Hepatic

- Renal

- Hypoglycemic

- Dysthyroid (hypothyroidism, thyrotoxicosis)

- Deficiency conditions (deficiency of B1, B12, folic acid, proteins)

- Industrial and household poisoning

- Iatrogenic cognitive impairment (use of anticholinergics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, neuroleptics, lithium salts, etc.)

- Neuroinfections and demyelinating diseases

- HIV-associated encephalopathy

- Spongiform encephalitis (Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease)

- Progressive panencephalitis

- Consequences of acute and subacute meningoencephalitis

- Progressive paralysis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Progressive dysimmune multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- Traumatic brain injury

- A brain tumor

- Liquorodynamic disorders

- Normotensive (aresorptive) hydrocephalus

- Other

| This section is not completed. You will help the project by correcting and expanding it. |

Reversible disorders[ | ]

In most chronic vascular and degenerative brain diseases, cognitive disorders are irreversible, but in cases where the cause of cognitive disorders is systemic metabolic disorders, correction of these disorders leads to the restoration of mental functions. In such cases they talk about reversible

cognitive disorders[2].

Reversible cognitive disorders include dysmetabolic encephalopathy, disorders of higher brain functions with normal pressure hydrocephalus and, in some cases, with a brain tumor; The cause of reversible disorders can also be anxiety-depressive disorders. Up to 5% of cases of cognitive impairment at the stage of dementia (and, apparently, a significantly larger percentage at the stage of mild and at the stage of moderate cognitive impairment) are completely reversible[2].

Since cognitive impairment does not always develop as a result of a primary brain disease, it is necessary, in addition to assessing the neurological status, a general physical examination of organs and systems. The necessary measures are a general blood and urine test, a study of the activity of liver transaminases and gamma-GT, thyroid hormones, a study of the concentration of bilirubin, albumin, creatinine and urea nitrogen, and, if possible, the concentration of vitamin B12 and folic acid. Restoration of cognitive functions after correction of metabolic disorders confirms the diagnosis[2].

Dissociative disorders

The mental life of a healthy person is integral and continuous. Memory cannot function without thinking, and attention cannot function without emotions. All mental functions are united into one whole and are reflected by the fundamental principle of the unity of consciousness.

Dissociation is a condition in which one or more mental processes are isolated from a single system and go beyond consciousness. The mental process functions independently of others, which is why personal identification and perception of one’s “I” are disrupted.

A synonym for dissociative disorder is conversion. This term is included in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, which defines it as a phenomenon arising as a result of internal interpersonal conflicts and manifested by symptoms of somatic diseases.

List of dissociative disorders:

- Fugue

- Dissociative amnesia.

- Dissociative identity disorder.

- Depersonalization.

- Unspecified dissociative disorder.

- Dissociative stupor.

- Convulsions.

- Mixed disorders.

Pathopsychological diagnosis for anxiety and dissociative disorders has 2 goals:

- Determines the form and degree of pathology.

- Differentiates anxiety and dissociative disorders from other psychiatric syndromes that have signs of increased anxiety and dissociation.

For diagnosis, clinical conversation and pathopsychological studies (MMPI, Spielberger scale, Hamilton scale) are used. Dissociative disorders are differentiated from schizophrenia, personality disorder, anxiety disorder and organic brain damage.

Notes[ | ]

- Zakharov V.V.

Management of patients with cognitive impairment // Breast Cancer. Archived November 26, 2011. - ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Zakharov V.V., Yakhno

N.N. Cognitive disorders in old and senile age: A manual for doctors. - Moscow, 2005. - ↑ 1 2 Yakhno N.N., Zakharov V.V.

Treatment of mild and moderate cognitive impairment // Breast Cancer. Archived November 27, 2011. - Bogolepova A.N.

Correction of the function of the cholinergic system in patients with cognitive disorders // Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry named after. S.S. Korsakov. - 2009. - No. 1. Archived on November 29, 2014.

Cognitive dysfunction in older cats

Due to improved nutrition, social living conditions, and progress in veterinary medicine, the lifespan of cats has increased to 15 years or more. In this regard, owners are faced with the natural aging process of their pet and are increasingly forced to turn to veterinarians with problems of physical and mental disorders that arise in pets as they age. Inevitable changes in the activity of biological processes occurring in the animal’s body lead to a progressive decline in cognitive functions and the appearance of altered forms of behavior, which is most often mistaken for a lack of training. Such behavioral problems raise the question of euthanizing their pet, which is a very significant psychological trauma.

Key words: brain, cognitive function, cognitive dysfunction, cat, environment.

Cognitive functions of the brain are the ability to understand, know, study, realize, perceive, remember and process information coming from the environment.

External manifestations of cognitive function are spatial orientation, memory and learning ability, cleanliness, recognition of the owner and identification of family members.

The material basis of thinking and associated orientations, emotions and adaptation to environmental conditions is the brain, in particular the special associative zones of the cerebral cortex.

The cerebral hemispheres are the anterior and largest part of the brain, which regulates acquired forms of behavior and makes up approximately 80% of the brain volume. [2]

The normal functioning of the cerebral cortex largely depends on the degree of blood supply and delivery of oxygen and glucose, since the brain consumes 20% of the total amount of oxygen in the body. The high percentage of polyunsaturated fatty acids and lower levels of endogenous antioxidant activity make it highly susceptible to oxidative damage. Cellular metabolic processes release reactive oxygen species, which can lead to oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, DNA and RNA, leading to neuronal death. Normally, the activity of endogenous antioxidants balances the production of toxic free radicals. However, with age, defense mechanisms begin to fail. Blood circulation deficiency leads to the development of the “steal” syndrome and the progressive death of both neurons directly and, primarily, glial cells responsible for the processes of learning and perception, causing the clinical implementation of cognitive disorders.

Therefore, it is natural that most neurological and vascular disorders are accompanied by impaired cognitive functions. [2.8]

Cognitive dysfunction is a complex of pathological conditions characterized by disruption of the higher nervous system, accompanied by a disorder in the processes of perception and analysis of information. In other words, these are various behavioral problems of old animals with a change in behavior pattern.

Specific behavioral disorders have received several names, namely: cognitive dysfunction, presenile depression, hyperaggressive syndrome, confused consciousness syndrome.

The development of cognitive impairment in elderly animals is based on age-related neurodegenerative changes in the cerebral cortex as a result of vascular disorders, accompanied by the accumulation of beta-amyloid and free radicals that have a neurotoxic effect. It is believed that in its symptoms and pathophysiological features, cognitive dysfunction in animals is similar to dementia such as Alzheimer's disease found in humans. [1]

In both diseases, the elderly brain develops abnormal deposition of Aβ in the brain parenchyma and walls of cerebral blood vessels. Aβ is a protein produced by the degradation of amyloid precursor protein. The prefrontal cortex is the first area affected, followed by the temporal cortex, hippocampus, and occipital cortex. Regardless of location, the amount and extent of Aβ deposits correlate with the severity of cognitive impairment. [9]

The basis for diagnosing age-related behavioral problems in an elderly animal is a behavioral history, exclusion of violations of social relationships between pets living in the same family, and differentiation of systemic disorders using laboratory diagnostics and visual diagnostics.

The basis of behavioral analysis is questions regarding the four main categories of behavioral changes associated with age-related cognitive dysfunction: disorientation, changes in response to environmental factors and social interaction, changes in the sleep/wake cycle, and disruption of house rules [3].

On average, after 7 years, cats become older and increasingly need care and attention, and if there are health problems, then additional care. Older patients require special treatment from the doctor. Older animals often have diseases characteristic of geriatric patients, often with a chronic, complicated course. At the same time, common clinical signs of cognitive decline in pets are designated by the abbreviation DISHA

a) Disorientation

b) Altered Interactions with people or other pets (change in interaction with people and other animals)

c) Altered Sleep-wake cycles

d) Housesoiling (failure to keep the house clean)

e) Activity changes - first a decrease, then an increase in restless behavior or aimless walking. [3.7]

Objective: To analyze data from various sources and show age-related statistics in the study of cognitive dysfunction in cats.

Methodology: To analyze this problem, the following articles were taken: “Cognitive Dysfunction in Cats: A Syndrome we Used to Dismiss as 'Old Age'” Gary M. Landsberg, Sagi Denenberg, Joseph A Araujo; “Cognitive dysfunction and the neurobiology of aging in cats” D. Gunn-Moore K. Moffat L.-A. Christie E. Head.

A general assessment of cognitive impairment can be given based on research by the authors of several articles. Thus, a study by one (K.M.) shows general behavioral changes in geriatric cats in private practice (Moffat and Landsberg 2003, KS Moffat, GM, Landsberg, E. Head, JA Araujo, B. Lindgren). In this study, cats 11 years of age and older who were brought in for a routine appointment (eg, vaccination or dental care) underwent a comprehensive medical and behavioral examination. Changes were then assessed by physical examination, as well as blood and urine tests. Those diseases that were systemic were excluded from the study.

An analysis was also conducted among 154 cats aged 11 and 21 years. The overall percentage of cats exhibiting geriatric behavioral changes was 44% (67/154). Nineteen of these cats with behavioral changes but not related to the underlying disease accounted for 36% (48/135). Behavioral changes also occurred among 50% (23/46) of cats 15 years of age and older, compared with 28% (25/89) of cats aged 11 to 14 years.

The most common behavioral changes observed in the 11–14 year age groups were changes in social interactions with people or other pets. In cats aged 15 years and older, changes were expressed in activities such as aimless activity and excessive vocalization.

Such data can be observed in people: from 65 to 70 years of age, dementia is observed in 1 to 3% of people and increases with age, so approximately 50% are people over 85 years of age (Porter et al. 2003). In this context, a 15-year-old cat is equivalent to an 85-year-old person.

Laboratory studies provide further evidence that cats are vulnerable to age-related cognitive decline. It is generally accepted that cognitive and motor functions decline with age, and experiments with cats have shown that this decline typically occurs beginning at age 10 (Harrison and Buchwald 1982, 1983, Levine and others 1987). In addition, they show increased sensitivity to environmental changes, which can lead to changes in eating and aggression. [5,6]

Conclusions: By analyzing statistical data in studies of cognitive dysfunction in cats, age-related changes were observed. Thus, the older the cat, the more severe the behavioral changes and cognitive impairment may be.

Literature:

- Kirk R., Bonagura D. Kirk's modern course of veterinary medicine. M.: Aquarium print, 2005

- Sidorov I.V., Kalugin V.V. [and others]. Handbook of treatment for dogs and cats. M.: Onyx 21st century, 2001. 576 p.

- Stekolikov A. A. Complex therapy and therapeutic techniques in veterinary medicine. St. Petersburg: Lan, 2007. 288 p.

- Carpenter RE, Pettifer GR, Tranquilli WJ Anesthesia for geriatric patients. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2008; 35:571–580.

- Gunn-Moore D., Moffat K., Christie L.-A., Head E. Cognitive dysfunction and the neurobiology of aging in cats; British Small Animal Veterinary Association (BSAVA), 2007

- Landsberg GM, Sagi Denenberg, Joseph A Araujo. Cognitive Dysfunction in Cats: A Syndrome we Used to Dismiss as 'Old Age' // Journal of Small Animal Practice. 2007; No. 48; pp. 546–553.

- Landsberg, G. M., Deporter, T., & Araujo, J. A. (2011). Clinical signs and management of anxiety, sleeplessness, and cognitive dysfunction in the senior pet. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice, 41(3), 565–90. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.03.017

- Skoumalova A, Rofina J, Schwippelova Z, et al. The role of free radicals in canine counterpart of senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Exp Gerontol 2003;38(6):711–719.

- Schmidt F, Boltze J, Jager C, et al. Detection and quantification of β-amyloid, pyroglutamil Aβ, and tau in aged canines. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2015;74(9):912–923.

Cognitive psychotherapy for personality disorders | Page 1 | Online library

Aaron Beck, Arthur Freeman

Cognitive psychotherapy for personality disorders

Acknowledgments

The publication of any book is associated with six important stages. The first of them is the nervous trembling and excitement when starting work on a book. At this early stage, various ideas are proposed, developed, modified, rejected, re-evaluated and restated. The reason for writing this book, like many of our other works, was clinical need combined with scientific interest. Patients with personality disorders were part of the clientele of almost every psychotherapist at our Center. The idea for this book came from weekly clinical seminars taught by Aaron T. Beck. As this idea developed, we received information and clinical experience from colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania and cognitive psychotherapy centers around the country, for which we are very grateful. Many of them became our co-authors and had a great influence on the direction and content of this book. Their brilliant minds and clinical insight bring a lively presentation to this book.

The second important stage in the birth of a book is the creation of a manuscript. Now the ideas have received concrete embodiment and are set out on paper. It is from this moment that the process of taking shape begins. Lawrence Trexler deserves all the credit for taking responsibility for reviewing and revising many of the chapters. This gave the project integrity and internal coherence.

The third stage begins when the manuscript is sent to the publishing house. Seymour Weingarten, editor-in-chief of the Guilford Press, has been a friend of cognitive psychotherapy for many years. (Seymour's vision and wisdom helped him publish the now classic Cognitive Therapy of Depression more than a decade ago.) Thanks to his help and encouragement, the book was able to be completed. Lead editor Judith Groman and editor Maria Strabery ensured that the manuscript was readable without compromising the content or focus of the text. Along with other employees of the publishing house, they completed work on the book.

The fourth stage is associated with the final editing and typesetting of the manuscript. Tina Inforzato did us a good service by repeatedly typing drafts of individual chapters. At the final stage, her abilities manifested themselves with particular brilliance. She collected bibliographic references scattered throughout the text, introduced many of the corrections we made into the text, and created a computer version of the book, from which the typographical typesetting was carried out. Karen Madden kept drafts of the book and deserves credit for her persistence. Donna Bautista helped Arthur Freeman stay organized despite his involvement in various projects. Barbara Marinelli, director of the Center for Cognitive Psychotherapy at the University of Pennsylvania, as always, took on the bulk of the work and allowed Beck to concentrate on the creation of this book and other scientific works. Dr. William F. Ranieri, chairman of the Board of Psychiatry at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey and the School of Osteopathic Medicine, was also a proponent of cognitive psychotherapy.

The final stage is publishing the book. So, dear colleagues, you are holding in your hands our book, which we hope will be useful to you.

We sincerely thank our life partners, Judge Phyllis Beck and Dr. Karen M. Simon, for their invaluable support.

The ongoing collaboration between the book's principal authors began as a student-teacher relationship and has evolved over the past 13 years with mutual respect, admiration, affection and friendship. We learned a lot from each other.

Finally, the patients we have worked with for years have allowed us to share their burden. It was their pain and suffering that prompted us to create the theory and methods called cognitive psychotherapy. They taught us a lot, and we hope that we were able to help them begin to live more fulfilling lives.

Aaron T. Beck

MD, Center for Cognitive Psychotherapy, University of Pennsylvania

Arthur Freeman,

Doctor of Education, Institute of Cognitive Psychotherapy, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey

Preface

In the decade since the publication of Aaron T. Beck and colleagues' book Cognitive Psychotherapy for Depression, cognitive psychotherapy has developed significantly. This method has become used to treat all common clinical syndromes, including anxiety, panic disorders and eating disorders. A study of the results of cognitive psychotherapy has shown its effectiveness in treating a wide range of clinical disorders. Cognitive psychotherapy has been applied to all ages (children, adolescents, geriatric patients) and has been used in a variety of settings (outpatient, inpatient, couples, groups, and families).

Using accumulated experience, this book is the first to examine the entire complex of cognitive psychotherapy for personality disorders.

The work of cognitive psychotherapists has received worldwide attention; Cognitive psychotherapy centers have been established throughout the United States and Europe. Based on a review of the work of clinical and counseling psychologists, Smith (1982) concluded that “the cognitive-behavioral approach is one of the strongest, if not the strongest, approach today” (p. 808). Interest in cognitive approaches among psychotherapists has increased 600% since 1973 (Norcross, Prochaska, & Gallagher, 1989).

Much of the research, theory, and clinical training in cognitive psychotherapy has been conducted at the Center for Cognitive Psychotherapy at the University of Pennsylvania or at centers run by those trained at the center. This work is based on seminars and debriefings of primary patients conducted by Beck over many years. When we decided to write a book in which we could present the understanding gained in the course of our work, we were aware that it would be impossible for one or two people to cover all the disorders under consideration. Therefore, to work on the book, we gathered a group of famous and talented psychotherapists who studied at the Center for Cognitive Psychotherapy, each of whom wrote a section on their specialization. We rejected the idea of an edited text that offered a series of disparate (or overly detailed) observations. In the interests of integrity and consistency of presentation, we have decided that this book will be the result of the joint efforts of all its authors.

Each author took responsibility for a specific topic or disorder. The draft material for each topic was then reviewed by all authors, which was intended to stimulate fruitful collaboration and promote consistency of presentation, after which the material was returned to the original author (or authors) for corrections and revision. Although this book is the result of the work of several authors, all of them are responsible for its contents. The main authors of each chapter will be listed below. Lawrence Trexler (PhD; Friends Hospital, Philadelphia, PA) provided integration, final editing, and coherence.

The book consists of two parts. The first part offers a broad overview of the historical, theoretical and psychotherapeutic aspects of the topic. This is followed by clinical chapters that detail individualized treatment for specific personality disorders. The clinical chapters correspond to the three groups described in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-R) (APA, 1987). Group A—disorders that are described as “strange or eccentric”—includes paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal personality disorders. Cluster B includes antisocial, borderline, histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders, which are described as “dramatic, emotional or erratic”. Cluster C includes “people who are obsessed with anxiety or fear,” who fall into the categories of avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, and passive-aggressive personality disorders.